Tag: Government

You often hear that if you’ve nothing to hide then government surveillance isn’t really something you should fear. It’s only the bad people that are targeted! Well….sorta. It is the case that (sometimes) ‘bad people’ are targeted. It’s also (often) the case that the definition of ‘bad people’ extends to ‘individuals exercising basic rights and freedoms.’ This is the lesson that a woman in the US learned: the FBI had secretly generated a 436 page report about her on the grounds that she and friends were organizing a local protest.

What’s more significant is the rampant inaccuracies in the report. The woman herself notes that,

I am repeatedly identified as a member of a different, more mainstream liberal activist group which I was not only not a part of, but actually fought with on countless occasions. To somehow not know that I detested this group of people was a colossal failure of intelligence-gathering. Hopefully the FBI has not gotten any better at figuring out who is a part of what, and that this has worked to the detriment of their surveillance of other activists. I am also repeatedly identified as being a part of campaigns that I was never involved with, or didn’t even know about, including protests in other cities. Maybe the FBI assumes every protester-type attends all other activist meetings and protests, like we’re just one big faceless monolith. “Oh, hey, you’re into this topic? Well, then, you’re probably into this topic, right? You’re all pinkos to us.”

In taking a general survey of all area activists, the files keep trying to draw non-existant connections between the most mainstream groups/people and the most radical, as though one was a front for the other. There are a few flyers from local events that have nothing to do with our campaign, including one posted to advertise a lefty discussion group at the university library. The FBI mentions that activists may be planning “direct action” at their meetings, which the document’s author clarifies means “illegal acts.” “Direct action” was then, and I’d say now, a term used to talk about civil disobedience and intentional arrests. While such things are illegal actions, the tone and context in these FBI files makes it sound like protesters got together and planned how to fly airplanes into buildings or something.

You see, it isn’t just the government surveillance that is itself pernicious. It’s the inaccuracies, mistaken profilings, and generalized suspicion cast upon citizens that can cause significant harms. It is the potential for these profiles to be developed and then sit indefinitely in government databases, just waiting to be used against law abiding ‘good’ citizens, that should give all citizens pause before they grant authorities more expansive surveillance powers.

I was surprised – and delighted – to see the Public Safety Critic for the Liberal Party of Canada recently come out against the use of IMSI catchers. Specifically, Francis Scarpaleggia said to Xtra!

The fact that the police do have technology that allows them to capture IMSIs, that means that they could theoretically, with that information, go to an ISP and get the identity of that person, even if the person’s just walking by innocently but they happen to be observing the crowd

This is a very, very good step in the right direction, and it’s terrific to see the technical concerns with forthcoming lawful access legislation actually rising to the attention of federal politicians. Hopefully we’ll see this kind of technical awareness rise all the way to statements in parliament and committee hearings on the legislation.

From the APPA’s letter to Google concerning Google’s new privacy police:

Initially, I would like to say that the TWG recognises Google’s efforts in making its privacy policies simpler and more understandable. Similarly, it notes Google’s education campaign announcing the changes. However, the TWG would suggest that combining personal information from across different services has the potential to significantly impact on the privacy of individuals. The group is also concerned that, in condensing and simplifying the privacy policies, important details may have been lost.

It’s a short, but valuable, letter for clarifying the principles that have privacy professionals concerned about Google’s policy changes. Go read it (.pdf link).

I’ve talked about trying to pull together a measurable comparison of Internet service in Canada for a while, but as of yet haven’t had the resources to build a tool which meets my criteria. Industry Canada had a similar idea for basic cell phone services. Specifically, the government department created a calculator to help Canadians easily compare text/voice plans across Canada’s various mobile provides. We’ll never see the calculator, however, because:

Internal departmental records released to Postmediareveal that Clement’s decision came after direct lobbying from the likes of Rogers Communications, Telus and the Canadian Wireless Telecommunications Association. Clement defended the decision to shut down the calculator by stating that it was “unfair” in that it didn’t include bundled services mainly offered by, yes, the big telecommunications providers.

It’s incredibly unfortunate that this tool wasn’t provided – it would have been of real assistance to the large number of Canadians that aren’t using bundled services. What’s worse is that, rather than providing the tool in a ‘basic’ state and then scaling it depending on demand (the approach planned by Industry Canada) the whole project was scrapped. Not even the source code has been made available. Consequently, Canadians paid a fortune to develop a tool which met its basic design specs, and have nothing to show for it save for a large government bill and the continued hassle of trying to decipher the cacophony of mobile phone plans. Carriers: 1 Canadians: 0.

An excellent piece from Bruce Schneier, in interview, concerning the relationship between trust and security. It’s short, so just go read it. For a taste:

My primary concerns are threats from the powerful. I’m not worried about criminals, even organised crime. Or terrorists, even organised terrorists. Those groups have always existed, always will, and they’ll always operate on the fringes of society. Societal pressures have done a good job of keeping them that way. It’s much more dangerous when those in power use that power to subvert trust. Specifically, I am thinking of governments and corporations.

Dan Goodin has a good piece on one of Bruce Schneier’s recent talks. From the top of the article:

Unlike the security risks posed by criminals, the threat from government regulation and data hoarders such as Apple and Google are more insidious because they threaten to alter the fabric of the Internet itself. They’re also different from traditional Internet threats because the perpetrators are shielded in a cloak of legitimacy. As a result, many people don’t recognize that their personal information or fortunes are more susceptible to these new forces than they ever were to the Russian Business Network or other Internet gangsters.

The notion that government – largely composed of security novices – large corporations, and a feudal security environment (where were trust Apple, Google, etc instead of having a generalizable good surveillance footprint) are key threats of security is not terribly new. This said, Bruce (as always) does a terrific job in explaining the issues in technically accurate ways that are simultaneously accessible to the layperson. Read the article; it’s well worth your time and will quickly demonstrate some of the ‘big’ threats to online security, privacy, and liberty.

Watch Out, It’s the Feds!

![]()

A cute representation. If it’s saved, and aggregated, it’s a sweet target for the Feds!

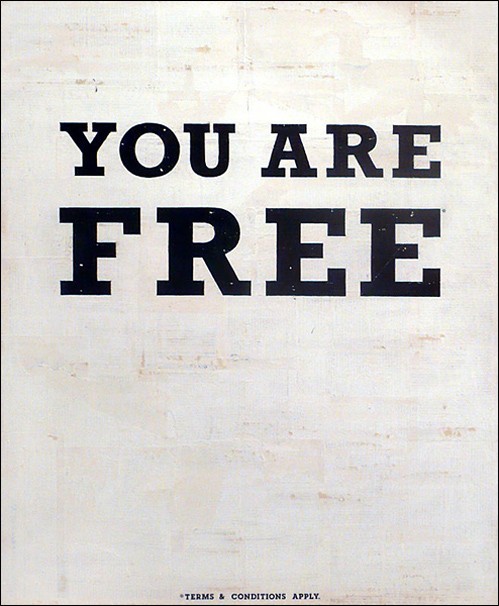

You are Free*

You should go read Chris’ paper, available at SSRN. Abstract below:

Today, when consumers evaluate potential telecommunications, Internet service or application providers – they are likely to consider several differentiating factors: The cost of service, the features offered as well as the providers’ reputation for network quality and customer service. The firms’ divergent approaches to privacy, and in particular, their policies regarding law enforcement and intelligence agencies’ access to their customers’ private data are not considered by consumers during the purchasing process – perhaps because it is practically impossible for anyone to discover this information.

A naïve reader might simply assume that the law gives companies very little wiggle room – when they are required to provide data, they must do so. This is true. However, companies have a huge amount of flexibility in the way they design their networks, in the amount of data they retain by default, the exigent circumstances in which they share data without a court order, and the degree to which they fight unreasonable requests. As such, there are substantial differences in the privacy practices of the major players in the telecommunications and Internet applications market: Some firms retain identifying data for years, while others retain no data at all; some voluntarily provide government agencies access to user data – one carrier even argued in court that its 1st amendment free speech rights guarantee it the right to do so, while other companies refuse to voluntarily disclose data without a court order; some companies charge government agencies when they request user data, while others disclose it for free. As such, a consumer’s decision to use a particular carrier or provider can significantly impact their privacy, and in some cases, their freedom.

Many companies profess their commitment to protecting their customers’ privacy, with some even arguing that they compete on their respective privacy practices. However, none seem to be willing to disclose, let alone compete on the extent to which they assist or resist government agencies’ surveillance activities. Because information about each firm’s practices is not publicly known, consumers cannot vote with their dollars, and pick service providers that best protect their privacy.

In this article, I focus on this lack of information and on the policy changes necessary to create market pressure for companies to put their customers’ privacy first. I outline the numerous ways in which companies currently assist the government, often going out of their way to provide easy access to their customers’ private communications and documents. I also highlight several ways in which some companies have opted to protect user privacy, and the specific product design decisions that firms can make that either protect their customers’ private data by default, or make it trivial for the government to engage in large scale surveillance. Finally, I make specific policy recommendations that, if implemented, will lead to the public disclosure of these privacy differences between companies, and hopefully, create further market incentives for firms to embrace privacy by design.